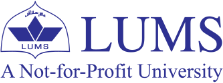

In Conversation with LUMS Alumna and Debut Novelist, Saba Karim Khan

During a candid conversation, LUMS BSc 2006 graduate of the Mushtaq Ahmad Gurmani School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Saba Karim Khan spoke about her debut novel, Skyfall, how she was inspired to find her ‘song’ and the experience of writing as a working woman and a parent. Khan is presently working at the New York University Abu Dhabi’s Social Research and Public Policy department within the Social Science Division. She has written for The Guardian, The Independent, Wasafiri (UK), HuffPost, Verso, Think Progress (USA), DAWN, The Friday Times and Express Tribune. She recently directed a documentary, Concrete Dreams: Some Roads Lead Home, which won many international awards.

What inspired you to write Skyfall? And what did you learn from writing it?

Too often, our jobs make us feel as if we’re cogs in a wheel, driven by the “check-at-the-end-of-the-month”; gratification, happiness become adjunct to that mechanical roster. Over time, frustration sprouts but we train our minds to believe rerouting isn’t an option. I certainly did! Then one winter, a guest speaker at NYU, the Headmaster from a school in England, quoted something which stopped me in my tracks: “Most men and women lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them,” he said. “What is your song?” He asked us to take five minutes and scribble our song on a piece of paper, before sharing it with the person sitting next to us. It felt daunting, trying to figure out my “song” in a matter of minutes, especially because in addition to my pipedreams, I had two tiny daughters: a one-year-old and a 2.5-week-old. Still, the Headmaster’s words shifted something fundamentally within me and they marked Skyfall’s inception that morning.

The journey of writing Skyfall offered a vital learning which I hope to carry with me into the future: when we dream our dreams, we tend to focus on their germination and culmination – the day we decide to embark on the journey and the point at which we see the finished product - both those stages yield the greatest excitement. However, as crucial as that initial and eventual thrill is, it isn’t enough. It’s the middle stages of keeping one’s head down, simply staying the course and doing the hard work - which is nonnegotiable. It mostly isn’t easy, nor does it feel particularly glorious. For instance, the experience with Skyfall involved alternating between my daughters and MS Word, those incessant hours of sitting in NYU’s library, inventing this make-belief world, being on holiday and still thinking, what might my characters be doing right now, I need to get back to writing, powering through 300 pages of the novel’s final edits during lockdown in a single day, watching chunks of Skyfall bite the dust to make it leaner, tighter – it’s messy, frustrating and rewarding in equal measure, there are days you get six words and days you get six thousand words – but embracing that chaos and forging ahead, I believe that’s what allows a book to come into being. Basically, I had to strip bare the glorious prospect of being a published author and fulfil the insane demands of writing whilst being a full-time working mother. The journey has shown me that there’s simply no short cut to clocking those hours and putting pen to paper.

What do you hope for readers to take away from this novel?

Hope, a better way of living. For readers to be able to imagine a world where co-existence is the currency, where the colour of my passport doesn’t determine my life chances. Even if Skyfall so much as sparks a conversation that interrupts things we’ve been conditioned to normalise – the immigration apocalypse, sexual violence, love-jihad – I’d say that’s nothing short of revolutionary. I’m already seeing reader reviews which mention how the issues in Skyfall make them seethe, how they find their eyes opened after reading it, so it’s very heartening.

What else is indispensable to the world of Skyfall is the embracing of vulnerability and imperfection; for readers to accept that some things can be broken yet beautiful – such as my home-country, Pakistan. That’s why, despite the dark spaces that Skyfall may shove readers into, its primary source remains the movement from darkness to light – it’s a metaphor repeatedly referenced within its pages. Hence, hopes and dreams are front-and-centre; maybe in ways more subtle than apparent, but you definitely arrive there, once the layers of gender violence, class conflict, love-jihad, the immigration apocalypse, have been fully unearthed.

What does the title of this book mean to you?

“Skyfall” literally means the last attempt you make against a group of people when outnumbered – that’s the spirit which crystallises the novel. The title is deeply personal to me; as middle-class girls growing up in “third-world” countries, we’re constantly taught to downsize our dreams so that they fit our reality. I read Skyfall as a ballad of resistance against that mindset, telling us that no one else should dictate our aukaat (worth). In short, Skyfall dares you with a single possibility: to amplify your reality so that it fits your dreams, instead of the other way around. That’s the real sort of courage that the journey of the female protagonist, Rania, hailing from Heera Mandi, illustrates in the book.

What kind of research did you do for this book, and how much time did you spend researching before beginning?

The beauty of a novel is that you can deliver a cavalcade of piercing truth about the world we live in, woven within the form of fiction. Skyfall is set in a dystopian world, and my research for it encapsulated travel, but not necessarily in a literal or conventional sense. It didn’t always involve boarding a flight, in fact often it meant going nowhere. Of course, literally visiting a new place opens up windows too, but I’m talking about travel through experience-sharing, which holds just as much power to transport you – a conversation, a visit to a local vendor, a street play, a ghazal, everything counts as research.

For instance, I spent several afternoons in Karachi at Tina Sani’s home, amidst chai and books, as she led me into the world of Ghalib and Faiz. I’m sure those conversations have subliminally made their way into Skyfall. Similarly, my experiences as a doc-filmmaker and an academic are undoubtedly conversant with my fiction writing. When I filmed for my debut documentary, Concrete Dreams, with young footballers in Lyari, I probably didn’t know at the time that those anecdotes were going to inform Skyfall. The same goes for the new online series I’ve directed with college survivors of sexual violence from South Asia or the research I’m doing on young Afghani men and their exposure to jihadist propaganda.

But most of all, I think the years I spent at LUMS, roaming the streets of Lahore, not the sanitized, touristy version but the raw, rough-around-the-edges city. Visiting Heera Mandi and Cuckoo’s Café and Shahjamal – those days and nights are fundamental to Skyfall. I have distinct memories of the dancing girls, those gulleys in the Walled City, the light bulbs switched on in the dingy Internet cafes. I believe it’s those experiences which helped me build an authentic realm and sense of place in the book, especially for Lahore. It reduced the risk of offering a stereotypical portrayal about this world, which otherwise stands at a far distance from me.

As this is your debut novel, what were some of your biggest qualms before publishing it?

I began as any typical outsider, pretty clueless. I don’t have access to an inner circle in publishing or a conventional degree in creative writing. All I had was this raging fire, the hunger to unearth my song. Unfortunately, as powerful a tag line as that might be, you realise fairly quickly that hunger on its own, doesn’t cut it.

Writing and publishing a novel feels different from penning a speedy op-ed or flash fiction – requiring a whole new level of blood, sweat and tears. Frankly, I was reluctant at the start myself, to write 300 pages without knowing if anything “tangible” would come of it. We always have our eye on the “prize”, which we mistakenly believe at the start is just publishing, finding your book on a bookshelf. Since I’d read and heard that the probability of getting debut fiction published is dangerously low, I secretly hoped someone would just take a shot on me and offer a publishing contract before I had to write the entire book. Of course, that wasn’t going to happen.

It also didn’t help that the publishing industry is still in its nascent stages in Pakistan – we don’t have literary agents, nor are we spoilt for choice with publishing houses. Grassroots attempts are being made to revive this industry but there’s still a long way to go, so where does one begin?

Left with little option, I decided to go piece-meal, breaking the process into baby steps. First, write a book which I believed was worth pitching. Second, research the agent world to see who might offer the right fit instead of going enmasse. Third, brace myself for rejection, which isn’t realistically possible, but to become somewhat thick-skinned about it! So, I researched my agent in a whole lot of detail and eventually emailed him my query one night along with a few sample chapters. He responded in under ten minutes and requested for the complete manuscript. There were several rounds of editing and re-editing after that, even before he sent it out to publishing houses. A few months later, the Bloomsbury offer came through. It definitely surprised me, in the most pleasant of ways, that a publishing house such as Bloomsbury was willing to take a shot on a debut fiction author who isn’t a social media celebrity, is in fact a woman of color, with no nepotistic access to the publishing industry. What’s more, throughout Skyfall’s making, there was little creative interference from Bloomsbury with structure and plot. It was incredibly eye-opening that fortunately, the story still matters, that maybe you don’t have to spend all your energies rounding up followers online and can spend some of that time actually writing.

What does literary success look like to you?

Literary success is such a nebulous goal, I don’t know what it means, beyond that peculiar and exhilarating sensation when a story puts my mind on fire or if I’m reading a passage from Skyfall to an intimate gathering, and someone in the room (or online), finds it chilling.

If I give it serious thought, perhaps it also means for my storytelling to be read on several levels, so it doesn’t appear deliberately esoteric or confined to intellectual echo-chambers. For my work to speak to my mother, basically!

For it to stand the test of time, in that sense, for it to be both timely and timeless.

And over the years, as I hone my craft, for those consuming my material to believe they are in hands they can trust, that I’m not short-changing them with a predictable, sanitised, fairy-tale arc. Instead, I’m opening windows into the greys and the chaos, no matter how nervous and uncomfortable that might make us.

And of course, for my royalties to keep me in cheap and cheerful lattes and sugar donuts. A Rolls-Royce is so last season, anyway!

What’s one book you would recommend to everyone, and why?

The Quran. I have read it a few times but without profoundly processing and interpreting it. I’d want to make that attempt myself and recommend it to others too, and agnostic to what faith they may or may not follow. Not just because it’s supposed to be a code of conduct, of life, but also to debunk some of the easily drawn up caricatures about Islam and its scripture – guns, bombs, the bearded terrorist – which continue floating in the West.

I have a clinching suspicion it will be a compelling ode to humanity and could help us imagine a better way of living.

You have said that you identify foremost as a storyteller. Why is that and how did you come to this realisation?

I’d say of all the labels people shove at me, storyteller and mother resonate most. At my core, I’ve always craved storytelling, even old-fashioned musings around a campfire, for two reasons: first, it forges an interface with other beings and lets you create something together. It opens up windows into new, sometimes unfamiliar worlds and feels like a form of travel without physically going somewhere. Second, I find a musicality in storytelling, like poetry in motion, which is deeply powerful. It took me a while, but I eventually embraced that lyrical quality to my own writing as well, because I realised that’s just how I tell my stories.

In retrospect, my experience with my debut documentary and novel, also hammers in how storytelling is one of the few pursuits that doesn’t become routinised; you can invent a million re-enchanting, soul-stirring ways of telling a tale and that’s precisely what I’ve tried to do with Skyfall. It’s felt like an experiment, a laboratory, throwing everything in the mix and waiting for the magic of storytelling to unfold.

What do you think are common traps for aspiring writers? What advice would you give to anyone aspiring to write fiction?

Putting off writing, that’s probably the foremost trap. Wanting guarantees about publishing, like I was hoping for, without investing in actual writing. Social media, another major trap most of us succumb to. The constant search for validation to our work. At some point, you have to discover your voice, embrace it and put it out in the universe. It is, after all, the unearthing of your song and should hold significance, irrespective of whether people love it or hate it. I’m slowly realising you cannot surrender the keys to your happiness, self-esteem and contentment to people hidden behind metallic screens. That’s why, the night before Skyfall released, I consciously put myself on the path to disbanding frames of expectation and the yearning for validation beyond the act of creating itself. I haven’t mastered it fully but I’m on the road.

The other realization that’s hit me has to do with the motivation for writing fiction – or any other creative project – that it has to be more than the “high” of fleeting fame or following. To consider from the get-go why you’re in this, because that’s what will see you through the long and often arduous process of writing the book and everything else that comes with the territory. Every day cannot bring glory and limelight.

Coming to writing about Pakistan specifically, the biggest trap I find is fitting Pakistan into a neat, exoticised, cookie-cutter template. As a result, when you read about Pakistan, it’s all things combustible: bearded terrorists, veiled, oppressed women, ragged children threading through the streets and nothing more. Of course, those elements exist, but there is so much more to the country. So, with Skyfall, I haven’t claimed any sort of representation. I’ve simply tried to strip open that caricatured mould to say, yes Pakistan is chaotic, but that’s how most real people and places are. As Miguel Syjuco’s author review describes it, I’ve whisked readers “through complex inner lives that bounce between Lahore and New York City, two hardscrabble and hopeful worlds that on these pages meet, finally, as equals.” Unfortunately, Pakistan is not usually presented as an “equal” in literature, so setting Skyfall against these vastly different yet overlapping backdrops (Lahore, Delhi and New York), elides nicely with rejecting the tropes I’ve witnessed Pakistani fiction often trapped within.